Menu Engineering, Optimization, and the Quiet Math That Keeps the Lights On

There is a moment every operator recognizes, even if they don’t always name it.

It’s not during a menu tasting, or a pricing meeting, or a consultant presentation with color-coded matrices. It happens later—when the room is full, the line is tight, tickets are stacked, and the restaurant feels busy in a way that should be profitable… but somehow isn’t.

At that moment, food cost percentages offer very little comfort.

The menu looks fine on paper. The items are popular. The sales reports show movement. And yet, the math at the end of the night doesn’t reflect the effort expended to earn it.

This is where menu engineering stops being an academic exercise and becomes a leadership discipline.

Because menus don’t fail in spreadsheets. They fail in service.

The Familiar Framework—and Its Limits

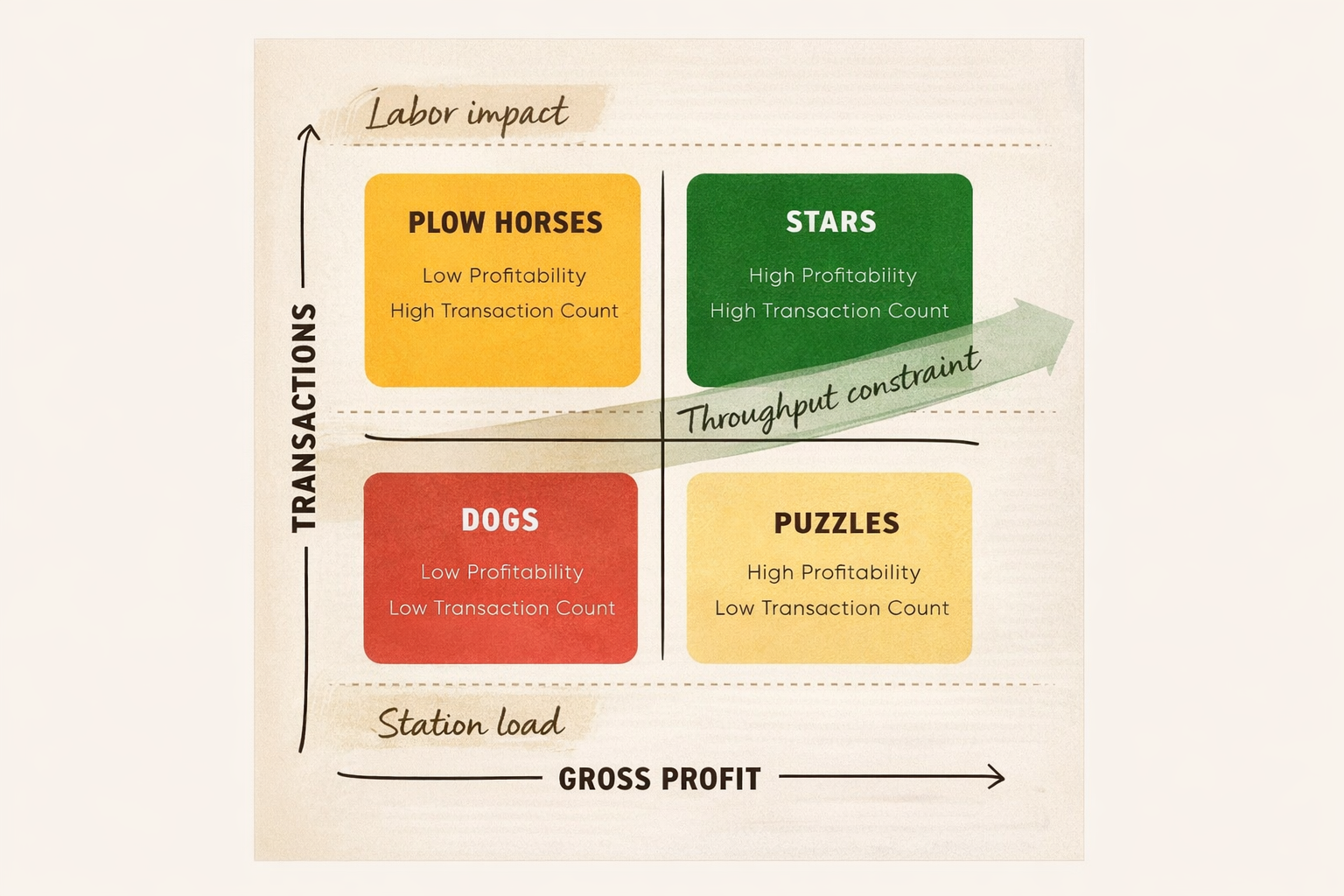

Most operators are introduced to menu engineering through a familiar framework: plotting menu items along two axes—popularity and profitability—and sorting them into neat categories. Stars. Plowhorses. Puzzles. Dogs.

The framework is not wrong. It’s useful. It forces discipline. It introduces the idea that not all menu items deserve equal attention or equal protection.

The classic menu engineering matrix. Useful as a diagnostic tool — but incomplete without labor impact, station load, and throughput context.

But like many tools borrowed from business theory, it can quietly mislead when applied without context.

The model assumes that if two items generate the same gross profit dollars, they are interchangeable. In real kitchens, they rarely are.

What the matrix doesn’t show is how those dollars are produced.

The Cost Percentage Illusion

Food and liquor cost percentages are seductive because they feel precise. They give the illusion of control. A lower percentage feels like a win, even when the dollars behind it are small.

A dish with a twenty percent food cost can look virtuous on a report while contributing very little to the operation’s actual financial health. Meanwhile, a dish with a higher cost percentage may quietly generate far more gross profit—simply because it sells at a higher price point and moves efficiently through the system.

Percentages reward cheapness. Restaurants survive on dollars.

This distinction becomes unavoidable when capacity—not demand—is the limiting factor.

Throughput: The Variable That Actually Decides the Night

Every restaurant has a constraint. Sometimes it’s obvious—a single grill, a lone fryer, one skilled sauté cook on a Friday night. Other times it’s more subtle: a plating step that requires attention, a sauce that can’t be rushed, a dish that demands explanation at the table.

That constraint defines throughput: how many profitable plates the operation can produce in a given window without breaking.

Throughput is not about speed for its own sake. It’s about flow. It’s the difference between a menu that looks profitable and one that actually performs under pressure.

Two items may show identical margins on paper. One moves through the line cleanly, finishes unattended, and clears the station. The other monopolizes attention, delays surrounding tickets, and slows the entire room.

When demand peaks, the second item doesn’t just underperform—it reduces the restaurant’s ability to generate revenue across the board.

This is why gross profit dollars per hour matter more than cost percentages per plate.

When “Stars” Become a Liability

Menu engineering often teaches us to protect our stars. But stars that overload the constraint stop being stars during peak service.

A popular, high-margin item that bottlenecks the line may feel indispensable—until it quietly caps revenue on your busiest nights. At that point, the question isn’t whether the dish is loved. It’s whether the operation can afford its footprint.

Experienced operators learn to read menus the way engineers read systems: not by what performs in isolation, but by what the system can support at scale.

Contribution Without Context Is Incomplete

Contribution margin is a better metric than cost percentage, but even contribution margin has blind spots if it’s divorced from execution.

A dish that produces strong gross profit dollars but requires disproportionate labor, skill concentration, or station load carries hidden costs that don’t show up neatly in reports. These costs appear instead as fatigue, errors, slower turns, and eventually—staff burnout.

Menus are not just pricing documents. They are training manuals, labor plans, and workflow diagrams disguised as paper.

Every item makes a demand on the system. The question is whether that demand is justified by what the item gives back.

The Quiet Role of Restraint

The most profitable menus are rarely the most ambitious. They are the most considered.

They understand that not every good idea deserves a permanent place. That novelty carries operational cost. That clarity sells better than cleverness. And that removing a dish can sometimes increase total revenue, even if that dish had loyal fans.

This is the uncomfortable part of menu engineering—the part that requires leadership rather than math.

It is easier to add than to subtract. Easier to defend a dish than to ask what it’s costing the rest of the menu.

Why This Is a Leadership Decision, Not a Technical One

Menu engineering is often delegated. Pricing is adjusted. Layouts are tweaked. Names are refined.

But the deeper questions—what the menu prioritizes, what it burdens, what it protects—are leadership questions. They reflect how an operator thinks about systems, people, and pressure.

A menu that ignores throughput is a menu that assumes infinite capacity. No restaurant has that luxury.

What the Model Misses

If the classic menu engineering framework were revisited for a more experienced audience, the structure would remain—but the analysis would deepen.

The quadrants would still exist. But overlaid quietly on top would be the realities that determine whether a restaurant survives peak service:

labor impact

station load

throughput constraint

These are not academic concepts. They are the forces operators negotiate every night, often without naming them.

Once named, they change how menus are read.

The Closing Thought

Menus don’t fail because operators don’t understand food cost. They fail because the menu asks more of the operation than the operation can sustainably give.

Percentages make us feel informed.

Dollars tell us whether the lights stay on.

Throughput tells us whether the system can endure success.

That’s the math that rarely makes it onto the page—but always shows up in the room.

This essay is part of Lessons from Table 8

For professional correspondence, the author may be reached at wzane@intelhospitality.com.